Stating the Obvious: On September 16th, the first section of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has ruled in the case X v. Poland (no. 20741/10) that the denial of custody of a child must not be based on the sexual orientation of a parent

Source: Anne Kompatscher, https://verfassungsblog.de/stating-the-obvious/

On September 16th, the first section of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has ruled in the case X v. Poland (no. 20741/10) that the denial of custody of a child must not be based on the sexual orientation of a parent. According to the Court, Poland has violated Article 14 (prohibition of discrimination) in conjunction with Article 8 (right to respect for private and family life) of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) when refusing the applicant full parental rights and custody of her youngest child. This ruling comes too late for the applicant, whose child has grown up, as the decision of the ECtHR took twelve years. Nevertheless, in the current Polish context, the finding of the Court on this case sends an important message.

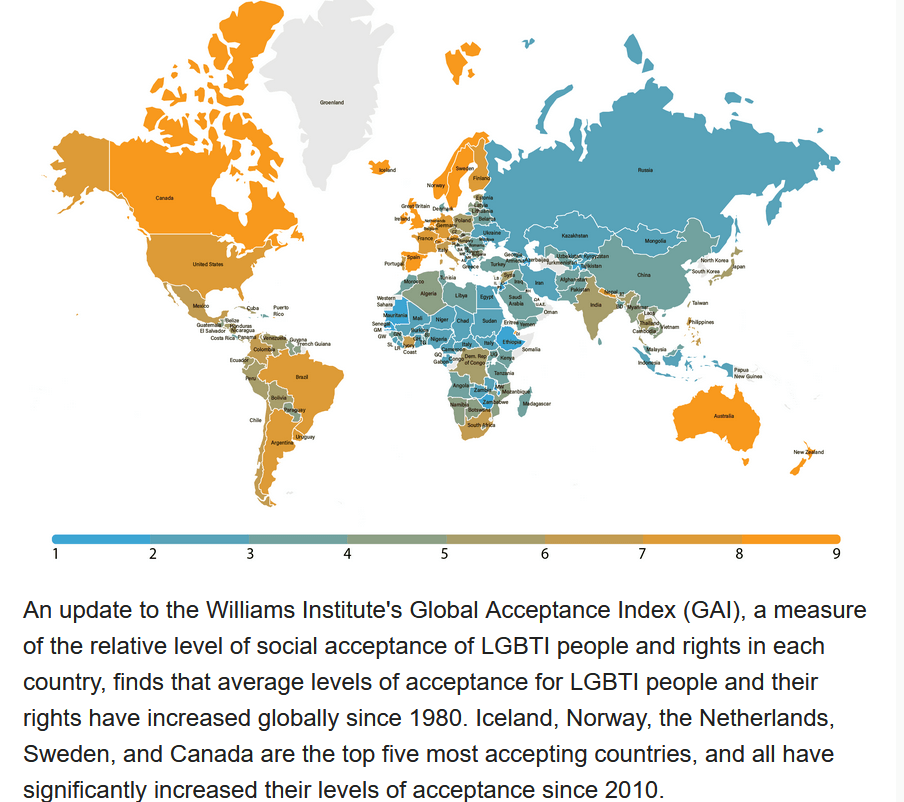

Poland currently dominates European and international news with negative headlines: the rule of law crisis, an escalating conflict with the Court of Justice of the EU, the dire consequences of strict abortion laws, the pushbacks of migrants at the Polish border to Belarus and last but not least the continuous undermining of the rights of the LGBTQIA+ community. According to a survey by the Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) of 2019 among LGBTQIA+ people in Poland, 68% of respondents find intolerance against them has risen in the last 5 years, and 96% find their government is not effectively combatting prejudice against them. Both of these numbers are the highest compared to all other EU countries.

In light of this context, or maybe because of it, it is worth having a close look at the recent decision of the ECtHR that finds Poland violating the parenting rights of the applicant, a member of the LGBTQIA+ community.

Facts of the case

The conflict between the applicant (X) and her husband over custody of their four children began in 2005. At the same time, X started a relationship with a woman, Z. Subsequently, when X and her husband divorced, X as the main-carer was granted full custody for the children.

In 2006, the applicant’s ex-husband wanted to change the custody arrangement bringing forward an expert opinion, according to which the applicant was not able to provide the necessary care to her children, as she was “excessively concentrating on herself and her relations with Z”.

The District Court restricted the parental rights of X and stated that she did not want “to abandon her excessive intimacy with Z to improve her relations with her children”. The Court gave the applicant’s ex-husband custody over the four children claiming that it would be better for the “wellbeing of the children”.

After a first failed attempt to revise the custody order, in 2009, the applicant requested to be granted parenting rights for the youngest child, D. In the second negative decision in this request, the Court underlined the fact that X was still in a relationship with Z who would also “spend the night in the applicant’s flat”. Furthermore, the Court stated the child needed a “male role model” for its development. The appeal of X was dismissed, with the remark that “the dismissal of her application was not on the grounds of the applicant’s sexual orientation”, but also that “the issue of raising a child in a same-sex relationship is very controversial”.

Following this decision, X decided to apply to the ECtHR.

A hardly surprising judgement of the ECtHR

In the judgement of September 16th, the ECtHR reiterates its well-established jurisprudence that Art. 14 provides a complementary provision as the Court can only declare discrimination related to rights guaranteed by the Convention. In the examined case, the discrimination relates to Art. 8, the Article guaranteeing the right to respect for private and family life.

X v. Poland is similar to a case of 1999, Salgueiro da Silva Mouta v. Portugal, (no. 33290/96) in which the ECtHR found a Portuguese Court had violated Art. 14 in conjunction with Art. 8 when basing the refusal of custody for Mr da Silva Mouta for his daughter on his sexual orientation. Despite the similarities of the cases, the ECtHR refers to this case only briefly when stating that Art. 14 and the prohibition of discrimination cover questions relating to sexual orientation and gender identity (Para. 70).

Even if sexual discrimination based on sexual orientation and parental rights of LGBTQIA+ is hardly a new concept for the ECtHR, the Court starts by establishing afresh that differential treatment needs a “reasonable justification” (Para. 69). The Court cites research as proof that children of rainbow families are not harmed by the fact of being raised by a same-sex couple. Hence differential treatment cannot be based on the assumption that the wellbeing of children is adversely affected by being raised in a rainbow family. It is not surprising that the Court considers it necessary to cite this research so extensively, even though it has already dealt with parental rights for LGBTQIA+ parents on several occasions before, for instance in Salgueiro da Silva Mouta v. Portugal (no. 33290/96) and Fretté v. France (no. 36515/97). The argumentation of the Polish Court shows that it has not acknowledged this ECtHR jurisprudence. The ECtHR then looks at the concrete case and establishes that the two parents in question have “similar parenting abilities and qualities” (Art. 84) and therefore a differential treatment cannot be justified.

The twofold argumentation of the ECtHR first looks generally at research concerning parenting abilities of homosexual parents and then assesses the abilities of the parents in the concrete case. Looking at the Polish judgments, it makes sense that the ECtHR stresses the fact that there is no prima facie assumption that homosexuals lack parenting abilities in principle. However, a custody case must depend on the best interest of the child and that needs to be evaluated by looking at the concrete case at hand.

Gendered Stereotypes

In Para. 45, the Court also refers to the Intra-American Court which in 2012 in Atala Riffo and Daughters v. Chile found that requiring a woman to not engage in or to end a relationship with another woman for the wellbeing of her children is based on a “traditional concept of women’s social role as a mother”.

The same can be said about the case before the ECtHR: the Polish Court’s assessment focused on the fact that X “remained in a relationship with Z”. The Polish Court concentrated extensively on the well-being of D with regard to the new homosexual relationship of his mother, whereas the new relationship of his father was not examined to the same extent. Hence, the Polish Court did not only discriminate against X because of her sexual orientation but adopted also a very gendered vision of what a mother should and should not do: X should focus on her children and not “excessively” on her relationship with Z. Contrarily, the child’s father’s new relationship was not discussed by the Polish Court. The ECtHR also recognises that the Polish Court repeated “at every stage of the proceedings” the importance of the “male role model” and found this to be discriminatory (Para. 90).

A not so impartial Polish Court

The first set of Polish proceedings regarding the custody was decided by the single Judge D.T. who had been opposing the relationship of X with Z since the very beginning. In the first appeal, the applicant submitted that Judge D.T. was biased, as she was a friend of her parents who were openly opposing that X was in a relationship with a woman. The District Court, which was the same Court as the one where D.T. sat, dismissed this challenge of bias. In later proceedings for amendments of the custody order, D.T again participated in the chamber deciding the case. The ECtHR, however, did not engage with this argument of the applicant regarding a possible violation of Art. 6 since the applicant had lodged this complaint too late. Nonetheless, this section puts to the fore personal biases of judges who have discriminatory views and are still in a position to judge over homosexual parents.

The dissenting opinion of judge Woityczek

The Polish ECtHR Justice Krzysztof Wojtyczek did not agree with the majority. According to him, no discrimination had happened. In his dissenting opinion, he states that in “international human-rights proceedings it is difficult to establish facts” and narrates further facts from the proceedings in front of the Polish Court that the ECtHR did not include in the final judgement. By turning the central question into one about facts, the Polish Judge refuses to recognise that the application did not concern the decision on refused custody as such but the justification that the Polish Court gave for the refusal. Basing the refusal on the fact that X was “excessively involved with Z” and that D needed a “male role model”, the Polish Court engaged in discriminatory reasoning, as the majority correctly held and the Justice Wojtyczek misses.

Context of the decision: discrimination against LGBTQIA+ in Poland

Notably, the ECtHR took its sweet time to decide the case: the judgement was issued twelve years after the dismissal of the appeal by the Polish regional Court. Meanwhile, the youngest two children had moved in with X and her partner, now with the approval of the applicant’s ex-husband. In a dispute about custody of children, such long periods between the application and the decision of a case are highly problematic: in the meantime, children grow, and an eventual decision will not have any real impact on the case at hand. The ECtHR envisions dealing with cases “within three years after they are brought”. X v Poland missed this mark by nine years.

It is not clear from the decision why the ECtHR took so long to decide. The decision of the ECtHR falls into a political situation in Poland that sees discrimination against LGBTQIA+ normalised and much exacerbated compared to the situation twelve years ago.

In the meantime, the current Polish government has spread more and more openly anti- LGBTQIA+ sentiment. Through terms as “LGBT ideology” and policies as the LGBT-Free zones, the Polish government encourages discrimination against members of the LGBTQIA+ community. With regard to the recent judicial reforms in Poland and the lack of judicial independence, LGBTQIA+ members also have to fear not being able to appeal against discriminatory behaviour of the Polish administration.

In stating the obvious, namely that the discrimination of a parent based on their sexual orientation infringes the ECHR, the ECtHR opposes such normalisation of discriminatory behaviour in Poland.

According to an inventory list from October 2020 by ILGA, the European umbrella organisation of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Associations, currently, twelve cases on Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression, and Sex Characteristics against Poland are lodged at the European Court of Justice and the ECtHR.

In the current political and societal Polish context, where structural discrimination against LGBTQIA+ is well embedded in hostile policies of the Polish government, the case X v. Poland may come too late for the applicant X but nevertheless sends an important message to Polish Courts: discriminating against LGBTQIA+ people when it comes to their parental rights infringes the ECHR.