Germany: Tax court in Münster has ruled that a gay couple has no right to deduct the costs of surrogacy from their taxes

Category Archives: Allgemein

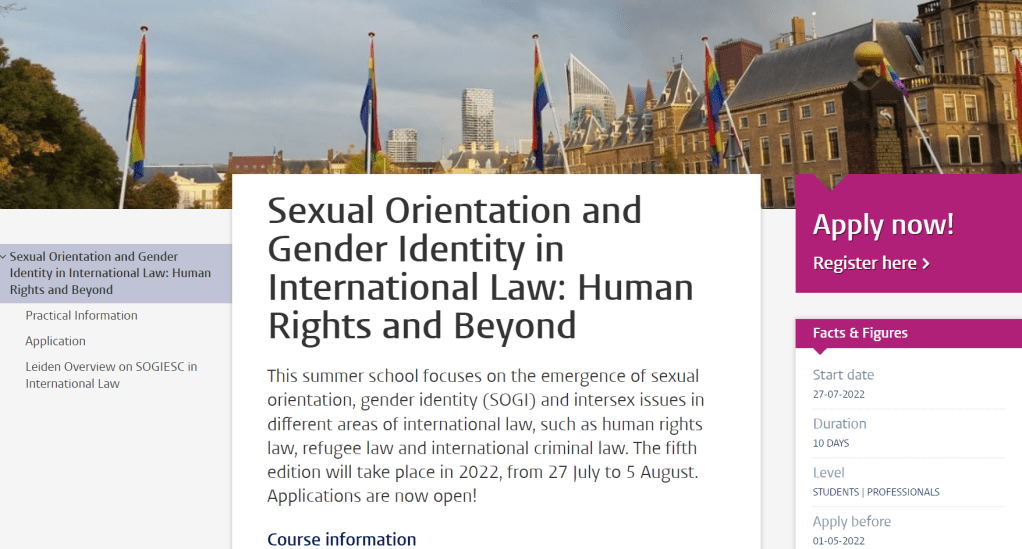

Register now for the Summer School on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in International Law (The Hague and Amsterdam, 27 July – 5 August 2022)

Register now for the Summer School on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in International Law (The Hague and Amsterdam, 27 July – 5 August 2022)

More information here: https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/education/study-programmes/summer-schools/sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity-in-international-law-human-rights-and-beyond

Lauch of the Leiden Overview on SOGIESC in International Law – free and online, Wednesday 26 January, 17:15 to 18:45 hrs

Lauch of the Leiden Overview on SOGIESC in International Law – free and online, Wednesday 26 January, 17:15 to 18:45 hrs

You are all invited to the official online launch on 26 January of the new online resource developed by Kees Waaldijk (professor of comparative sexual orientation law at Leiden University’s Grotius Centre) and Waruguru Gaitho (human rights lawyer and academic, currently working at Leiden University’s Van Vollenhoven Institute): the Leiden Overview on SOGIESC in International Law.

Subtitle: A list of online introductory video/audio/reading materials for anyone interested in the international legal aspects of sexual orientation, gender identity/expression or sex characteristics – and in particular for anyone (considering) taking part in Leiden University’s Summer School on SOGI in International Law,

see: www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/education/study-programmes/summer-schools/sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity-in-international-law-human-rights-and-beyond/leiden-overview-on-sogiesc-in-international-law.

On Wednesday 26 January, 17:15 to 18:45 hrs, this Leiden Overview will be presented to two key players in this field of law: Flávia Piovesan (Rapporteur on the Rights of LGBTI Persons, member of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and professor of Constitutional Law and Humans Rights in São Paulo) & Gurchaten Sandhu (who works on non-discrimination at the ILO, and is President of UN-GLOBE, the organization advocating for the equality of LGBTIQ+ personnel and dependents in the UN system). For more information about the four speakers mentioned, and for registration for this online launch,

Twitter: https://twitter.com/LeidenLaw/status/1479067881816137731?s=20

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeidenLawSchool/posts/10159857791041392

Please spread the word about this event – and about the Summer School on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in International Law (The Hague and Amsterdam, 27 July – 5 August 2022).

France removes restrictions on gay blood donors

France removes restrictions on gay blood donors

France is to allow LGBT citizens to donate blood without “discriminatory” conditions, the country’s health ministry has announced.

From 16 March, blood donation will be open to all French citizens regardless of their sexual orientation, health minister Olivier Véran said.

Read: https://www.euronews.com/2022/01/12/france-removes-restrictions-on-gay-blood-donors

New article: LGBT Rights as Mega-Politics: Litigating Before the ECTHR

New article: LGBT Rights as Mega-Politics: Litigating Before the ECTHR

The latest issue of Law and Contemporary Problems (Vol 84, no. 4, 2021) is a special issue on “The International Adjudication of Mega-Politics.” Contents include:

- Laurence R. Helfer & Clare Ryan, LGBT Rights as Mega-Politics: Litigating Before the ECTHR

The “gay cake” case – guest post on (ECHR Sexual Orientation Blog) Lee v the UK (Posted: 07 Jan 2022 09:01 AM PST by Dr. Silvia Falcetta

The “gay cake” case – guest post on (ECHR Sexual Orientation Blog) Lee v the UK (Posted: 07 Jan 2022 09:01 AM PST by Dr. Silvia Falcetta

| The “gay cake” case – guest post on Lee v the UK Posted: 07 Jan 2022 09:01 AM PST Lee v the United Kingdom – guest post by Dr. Silvia Falcetta, University of YorkThe Fourth Section of the European Court of Human Rights has published its decision in the case of Lee v the United Kingdom.This case concerns the refusal of a bakery, the Ashers Baking Company Limited, and its Christian owners to provide the applicant with a cake with the words ‘Support Gay Marriage’ iced on it.The Court declared the application inadmissible by a majority on the grounds of non-exhaustion of domestic remedies.Facts of the case In May 2014, the applicant, Mr Gareth Lee, decided to order a cake from a bakery, Ashers Baking Company Limited (‘Ashers’), with a picture of two popular characters from a children’s television show, the logo of ‘QueerSpace’ (an LGBTIQ organisation the applicant is associated with) and the words ‘Support Gay Marriage’. Mr Lee’s order was received without comment, he paid for and received a receipt for his purchase. However, a few days later he received a telephone call from Ashers in which they explained that they were a Christian business and that they should not have taken the order.With the support of the Equality Commission for Northern Ireland, Mr Lee brought an action in the County Court for breach of statutory duty in and about the provision of goods, facilities and services against Ashers, as a limited company, and its owners, Mr and Mrs McArthur (‘the McArthurs’). Mr Lee claimed that he had been discriminated against contrary to the provisions of The Equality Act (Sexual Orientation) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2006 (‘the 2006 Regulations’) and/or The Fair Employment and Treatment (Northern Ireland) Order 1998 (‘the 1998 Order’), which prohibit direct or indirect discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation, political opinion or religious beliefs.The County Court proceedingsThe County Court considered whether Mr Lee had been discriminated against on grounds of sexual orientation and/or political opinion. It concluded that the McArthurs had directly discriminated against Mr Lee on the grounds of ‘his sexual orientation’ (para 13) and on the grounds of his ‘religious belief or political opinion’ (para 14).In respect of the sexual orientation claim, the County Court accepted that the McArthurs’ deeply held religious beliefs were genuine, but it noted that Ashers was not a religious organisation, rather a commercial business run for profit. Whilst the 2006 Regulations provide some exceptions for religious organisations, Christian-owned businesses are excluded from such exceptions. As a consequence, the County Court concluded that the actions of the McArthurs could not be justified under the 2006 Regulations.In respect of the political beliefs claim, the County Court held that, in the context of the ongoing debate on same-sex marriage in Northern Ireland, Mr Lee’s support for same-sex marriage amounted to a political opinion. Thus, in refusing to fulfil Mr Lee’s order the McArthurs had directly discriminated against him in a way that was incompatible with the 1998 Order.The McArthurs invited the County Court to ‘read down the provisions of the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order in a manner which was compatible with their Convention rights’ under section 3 of the Human Rights Act or, if that was not possible, ‘to disapply the relevant provisions of the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order’ (para 15). In this respect, the County Court accepted that Article 9 of the Convention was engaged in this case, but it ultimately concluded that whilst the McArthurs ‘were entitled to hold their genuine and deeply held religious beliefs and to manifest them, they could not do so in the commercial sphere if this would be contrary to the rights of others’ which included Mr Lee’s right not to be discriminated against on the grounds of his sexual orientation (para 16). The County Court further held that the McArthurs had not been required to ‘support, promote or endorse’ Mr Lee’s views and it therefore concluded that Article 10 was not engaged in this case (para 18).The Court of Appeal proceedingsThe Court of Appeal confirmed the findings of the County Court and found that there had been associative direct discrimination against the applicant on the ground of sexual orientation (that is, the applicant had been discriminated against on the basis of his association with the gay and bisexual community). Moreover, the Court of Appeal agreed with the County Court that the McArthurs had not been in any way required to promote or support same-sex marriage by fulfilling Mr Lee’s order (para 22).The Supreme Court proceedingsThe UK Supreme Court (UKSC) disagreed with the lower courts, and it unanimously held that the defendants’ refusal to fulfil Mr Lee’s order did not constitute unlawful discrimination.In respect of the sexual orientation claim, the UKSC disagreed with the County Court, and it held that Ashers had cancelled the order not on the basis of Mr Lee’s actual or presumed sexual orientation, but because they oppose same-sex marriage. The UKSC further disputed the Court of Appeal’s finding that Ashers had cancelled the order because the applicant was likely to associate with the gay and bisexual community, of which the McArthurs disapproved. Indeed, the UKSC established that ‘[i]n a nutshell, [the McArthurs’] objection was to the message and not to any particular person or persons’ (para 27).The UKSC further determined that the McArthurs’ objection was to ‘being required to promote the message on the cake’ and ‘the less favourable treatment was afforded to the message not to the man’. Thus, it concluded that Ashers had not discriminated against Mr Lee because of the owners’ religious beliefs (para 30).In respect of the political beliefs claim, the UKSC did not exclude that Mr Lee may have been discriminated against on the basis of his political opinions. However, the UKSC went on to consider the McArthurs’ rights under Article 9 and Article 10 of the Convention upon the effect of the 1998 Order, and it found that the 1998 Order ‘should not be read or given effect in such a way as to compel providers of goods, facilities and services to express a message with which they disagree unless justification is shown for doing so’ (para 34). Since no justification had been shown for justifying the compelled speech, the UKSC held that there had been no unlawful discrimination and dismissed Mr Lee’s claim for breach of statutory duty.In conclusion, the UKSC allowed the defendants’ appeal and set aside the declarations and order for damages made by the County Court.Complaints to the CourtThe applicant claimed that the decision of the UKSC to dismiss his claim for breach of statutory duty violated his rights under Article 8, Article 9, and Article 10, alone and taken in conjunction with Article 14 of the Convention.The Court’s assessmentThe Court started by considering whether the applicant had exhausted all domestic remedies before lodging his application under the Convention.The Court noted that the applicant had formulated his claim with reference to the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order, without expressly invoking any of his Convention rights at any point in the domestic proceedings. In this respect, the Court reiterated the subsidiary nature of the Convention machinery and the general principle that any complaint presented before it ‘must have been aired, either explicitly or in substance, before the national courts’ (para 68). The Court took note of the applicant’s argument that a) he had raised his Convention arguments ‘in substance’ in domestic proceedings, since the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order had been enacted to protect his rights under Articles 8, 9, 10 and 14 of the Convention; and b) that the violations complained of before the Court had ‘only crystallised with the handing down of the judgment of the Supreme Court’ (para 69). Nevertheless, the Court was not persuaded by these arguments for two key reasons.First, the Court held that the relevant provisions in the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order cannot be said to ‘protect consumers’ substantive rights under Articles 8, 9 or 10 of the Convention’ (para 70). The Court acknowledged that the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order had been enacted in order to protect the Convention rights of consumers, but it also noted that those provisions, unlike the Convention, protect consumers in a ‘very limited way’ and concern only discrimination in access to goods and services (para 70). On this basis, the Court denied that the applicant has raised his rights protected under Article 8, Article 9 and Article 10 in substance during the domestic proceedings.In respect of whether the applicant had invoked Article 8, Article 9 and Article 10 taken together with Article 14, the Court acknowledged that the applicant had raised the issue of whether he had been discriminated against on the basis of his sexual orientation and/or political beliefs in the domestic proceedings. However, the Court reiterated the ancillary nature of Article 14 and recalled that ‘there can be no room for its application unless the facts at issue fall within the ambit of one or more substantive Convention rights’ (para 72). The Court did not exclude that the facts of the case could fall within the ambit of Convention rights, but it ultimately held that by relying solely on domestic law the applicant had ‘deprived’ the domestic courts of the opportunity to consider themselves whether the facts of the case engaged his rights under Article 8, Article 9 and Article 10 before lodging his application with the Court (para 74).Second, the Court noted that domestic courts had been tasked with balancing the applicant’s rights under the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order against the McArthurs’ rights under Articles 9 and 10 of the Convention, but at no point had the domestic courts been tasked with balancing the applicant’s Convention rights against the McArthurs’ Convention rights. Notably, the Court compared the approach followed by the applicant throughout the domestic proceedings with that followed by the McArthurs and concluded that the applicant had not provided a ‘satisfactory explanation’ for not advancing his Convention rights before domestic courts (para 77). Unlike the applicant, the McArthurs had effectively relied on their Convention rights throughout the domestic proceedings and had asked the courts to either read down the provisions of the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order in a manner which was compatible with their Convention rights or, if that was not possible, to disapply the relevant provisions of the 2006 Regulations and the 1998 Order.On this basis the Court held that in cases where ‘the applicant is complaining that the domestic courts failed properly to balance his Convention rights against those of another private individual, who had expressly advanced his or her Convention rights throughout the domestic proceedings, it is axiomatic that the applicant’s Convention rights should also have been invoked expressly before the domestic courts’ and it concluded that ‘[i]n choosing not to rely on his Convention rights, the applicant deprived the domestic courts of the opportunity to consider both the applicability of Article 14 to his case and the substantive merits of the Convention complaints on which he now relies’ and he invited the Court to ‘usurp the role of the domestic courts by addressing these issues itself’ (para 77).In conclusion, the Court considered that the applicant has failed to exhaust domestic remedies in respect of his complaints under Articles 8, 9 and 10 of the Convention, read alone and in conjunction with Article 14.Two brief considerationsA peculiar interpretation of the relationship between the Human Rights Act 1998 and the ConventionThis decision hands down a peculiar interpretation of the relationship between the Human Rights Act 1998 and the Convention, that no doubt will draw criticism and raise debate.According to the Court’s reasoning, when reading and giving effect to primary and subordinate legislation domestic courts seem required to take into account the Convention rights of the litigants only if the litigants themselves invoke those rights. When reading the Court’s decision, one may reasonably get the impression that under the Human Rights Act 1998 domestic courts are not allowed to consider litigants’ Convention rights motu proprio. However, section 3 of the Human Rights Act 1998 does not mention any such constraint and simply states ‘[s]o far as it is possible to do so, primary legislation and subordinate legislation must be read and given effect in a way which is compatible with the Convention rights’. Nothing in this provision indicates that considerations of the relationship between domestic legislation and the Convention are conditional on the arguments made by litigants. On the contrary, a plain reading of this provision suggests that, whenever it is possible to do so, domestic courts should read and give effect to primary and secondary legislation in a way that is compatible with the Convention of their own accord.As a consequence, it remains unclear why the Court assumed that the UKSC could not assess motu proprio whether domestic legislation had been interpreted in a way that adequately protected Mr Lee’s Convention rights.A cautious approach?This decision arguably signals the Court’s intention to maintain a cautious approach on complaints concerning a ‘clash’ between the right of individuals to freedom of religion and the right of LGBTIQ individuals to not be discriminated against in accessing goods, facilities, and services.Whilst not examining the merits of the applicant’s complaint, the Court acknowledged that a balancing exercise of the applicant’s Convention rights against the McArthurs’ Convention rights would be ‘a matter of great import and sensitivity to both LGBTIQ communities and to faith communities’, especially in the context of Norther Ireland where ‘there is a large and strong faith community, where the LGBTIQ community has endured a history of considerable discrimination and intimidation, and where conflict between the rights of these two communities has long been a feature of public debate’ (para 75). As a general principle, the Court held that similar disputes must be resolved ‘with tolerance, without undue disrespect to sincere religious beliefs, and without subjecting gay persons to indignities when they seek goods and services in an open market’ (para 75). However, the Court also reiterated that in the light of the ‘heightened sensitivity of the balancing exercise in the particular national context’ the domestic courts would be better placed than the international judge to strike the balance between Mr Lee’s competing Convention rights and the McArthurs’ Convention rights (para 76).On this basis, it seems likely that, even if Mr Lee’s complaint had been declared admissible, the Court would have deferred to the margin of appreciation available to domestic authorities and confirmed the findings of the UKSC. |

Interesting New Journal Article: Legal Violence and (In)Visible Families: How Law Shapes and Erases Family Life in SOGI Asylum in Europe

Interesting New Journal Article: Legal Violence and (In)Visible Families: How Law Shapes and Erases Family Life in SOGI Asylum in Europe

Carmelo Danisi, Nuno FerreiraHuman Rights Law Review, Volume 22, Issue 1, March 2022, ngab020, https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngab020

Published: 06 August 2021

- Abstract Studies on the Refugee Convention have paid very limited attention to the notion of family and family rights of asylum claimants in connection with asylum claims based on sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI). Drawing on the notion of ‘legal violence’, this article demonstrates the injurious cumulative effect that a heteronormative, homonormative and Western-centered formulation and implementation of asylum and refugee law has on SOGI claimants when it comes to intimate and family relationships. By relying on a solid body of primary and secondary data, it explores the invisibility of SOGI claimants and refugees’ families and how that invisibility is normalized by European legal frameworks, such as the Dublin (III) Regulation and Family Reunification Directive. To end this ‘legal violence’ and reconnect asylum systems with the lived experiences of SOGI claimants, a principled approach based on human rights and specifically the right to respect for family life is suggested.

Natalie Alkiviadou: A Missed Opportunity for LGBTQ Rights (on Verfassungsblog)

Natalie Alkiviadou: A Missed Opportunity for LGBTQ Rights (on Verfassungsblog)

Source: https://verfassungsblog.de/a-missed-opportunity-for-lgbtq-rights/

A few days ago, the British activist Gareth Lee failed with his complaint before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). The Court declared the application inadmissible as Lee had not claimed the violation of rights under the European Convention on Human Rights in any of the national court proceedings and thus had not exhausted all national remedies. Lee v. the United Kingdom really was a missed opportunity for Europe’s regional human rights court to address the issue of homophobia in the context of access to goods and services.

Lee v. the United Kingdom

In 2014, a Northern Irish bakery had refused to deliver a cake ordered by Lee with the words „Support Gay Marriage“ and the QueerSpace logo on it. The applicant was told by the bakery that his cake could not be made because the bakery was a Christian business. The case reached the Supreme Court, which found no discrimination against the applicant on grounds of sexual orientation. It held that the bakery’s objection related to the cake’s message and not to the applicant’s sexual orientation. Lee complained to the ECtHR arguing that his rights under Article 8 (private life), Article 9 (freedom of religion) and Article 10 (freedom of expression), alone and in conjunction with Article 14, had been violated.

Now, the ECtHR declared the case inadmissible. Relying on cases such as Azinas v. Cyprus, the Court referred to the Convention’s subsidiary character. In Azinas, for example, the Grand Chamber had found that ‘It would be contrary to the subsidiary character of the Convention system if an applicant, ignoring a possible Convention argument, could rely on some other ground before the national authorities for challenging an impugned measure, but then lodge an application before the Court on the basis of the Convention argument.’

In Lee, the Court also underlined that ‘it is not immediately apparent how the findings of the Supreme Court and the consequences of those findings for the applicant either constitute one of the modalities of or are linked to the exercise of a right guaranteed by any of those Articles.’

The Court noted that Lee did not invoke his Convention rights expressly at any point in the domestic proceedings and stressed that it was not convinced by his arguments, namely that the domestic law provisions on which he relied existed to protect his aforementioned rights and that the violations complained about only crystallized with the judgement of the Supreme Court, after which there were no further available remedies on a national level.

It appears to me that through the above reasoning, the Court puts all its energy into avoiding answering important questions, offering no analysis of any of the articles cited by the applicant, and thus leaving key legal questions unanswered. The deputy director of the Committee on the Administration of Justice (a third party intervener in the case) described this as a ‘missed opportunity’ for the ECtHR to ‘clarify its case law on sexual orientation and discrimination in the private sector.’

The US Cake Case

A brief discussion of the US Supreme Court jurisprudence is merited, since, in Lee, both the Supreme Court and the ECtHR referred to the 2018 case of Masterpiece Cakeshop Ltd v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission. This case involved a baker’s refusal to make a cake for the marriage celebrations of a same-sex couple due to his religious beliefs. The lower courts had all found in favour of the clients because the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act (2015) prohibits businesses from discriminating on the basis of sexual orientation. However, the strong First Amendment tradition of the country meant that the direction changed at the Supreme Court. The First Amendment provides that ‘Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.’

As such, free speech holds a particularly strong position in the US legal order. As a result, in Masterpiece, with two dissenting opinions, the Supreme Court found that the Commission’s position violated the State’s prohibition under the First Amendment to pass laws which are founded on hostility to a religion or religious viewpoint. The Court underlined that the baker, Philips, was ‘entitled to a neutral and respectful consideration of his claims’ which was ‘compromised’ due to the Commission’s demonstration of ‘impermissible hostility’ towards his religious beliefs. In citing this case, the ECtHR in Lee referred to the US Supreme Court’s position that such disputes ‘must be resolved with tolerance, without undue disrespect to sincere religious beliefs and without subjecting gay persons to indignities when they seek goods and services.’ How the ECtHR actually implemented this is unclear, given the stringency it applied to the admissibility requirements.

Interestingly, at the time of the US ‘cake case’, another judgement was passed, Arlene’s Flowers v. State of Washington. This case dealt with a florist who refused to arrange the flowers for a same-sex marriage. The US Supreme Court was asked to take up the case in 2017. It sent it back down to the Washington Supreme Court, with instructions to reconsider it given the Masterpiece judgement. In 2019, the Washington Supreme Court ruled against the florist for a second time. She asked the US Supreme Court to hear her case, but it rejected her request. A significant element in this case (had it been heard by the Supreme Court) and other future cases, would have been the court’s legal analysis of ‘the nexus between the First Amendment and anti-discrimination laws in the absence of (alleged) hostility on the part of lower courts or bodies’. This is because the Masterpiece case dealt extensively with the alleged hostility the Commission had shown towards the baker and his beliefs. This took up much of the Court’s reasoning. The emphasis on the alleged hostility may have stood in the way of a more extensive assessment of the rights of the LGBTQ community to access goods and services.

Goods, Services and Homophobia

In 2010, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted a resolution entitled ‘Discrimination on the Basis of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity.’ This calls on States Parties to, inter alia, protect the LGBTQ community from discrimination (making specific reference to the facilitation of access to goods and services by transgender persons) and to ensure effective judicial involvement where discrimination cases arise. The 2010 Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers on ‘Measures to Combat Discrimination on Grounds of Sexual Orientation or Gender Identity’ looks at issues such as free speech, hate crime and hate speech, whilst the area of ‘goods and services’ is restricted to health, housing and education. On a European Union (EU) level, things are relatively bleak in terms of protection against discrimination of LGBTQ communities when it comes to goods and services. The Racial Equality Directive encompasses equal treatment in relation to employment, vocational training, social protection and social advantages, education and access to and supply of goods and services. In contrast, the General Framework for Equal Treatment in Employment and Occupation, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of other characteristics, such as sexual orientation, is limited to the workplace. This distinction has led to the 2000 directives carrying ‘an aura of unfinished business,’ with no convincing explanation for this difference having been put forth yet. In 2014, the European Parliament passed the ‘Roadmap against Homophobia and Discrimination on Grounds of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity.’ In it, the Parliament highlights its belief that the EU ‘currently lacks a comprehensive policy to protect the fundamental rights of LGBTQ people.’ For this reason, it called on the Commission, Member States and the relevant agencies to work jointly on a comprehensive multiannual policy to protect the fundamental rights of LGBTQ persons.

Undoubtedly, then, the differences between the directives’ applicability and purpose affect the quality and efficacy of any national law that transposes the directives as they stand. In brief, EU non-discrimination protection on the basis of sexual orientation ‘demonstrates a hierarchy of what the EU considers as significant enough to be actionable.’

A Missed Opportunity

Lee really was a missed opportunity for Europe’s regional human rights court to address the issue of homophobia in the context of access to goods and services, particularly in the absence of an EU framework. The ruling could have been a guiding light not only for a post-EU United Kingdom but also for the other members of the Council of Europe. Moreover, it is another thorn in the side of the current framework in which the rights of the LGBTQ community are less protected than those of other communities.

Join us for the training to pilot the LGBTI Inclusion Index: a UNDP-led initiative

Join us for the training to pilot the LGBTI Inclusion Index: a UNDP-led initiative

Join us for the training to pilot the LGBTI Inclusion Index: a UNDP-led initiative developed in partnership with LGBTI+ community organizations, multilateral organizations, governments, academia, and the private sector. The training will prepare participants to create a pilot version of the Index.

The LGBTI Inclusion Index aspires to measure the inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex people across five strategic areas: security and violence, health, education, civic and political participation, and economic empowerment. In doing so, the Index will rely on 51 proposed indicators, which are compatible with the target indicators of the Sustainable Development Goals.

The training consists of two parts: (1) five self-paced, pre-recorded training modules (2.5 hours total), and (2) one live session adjusted to different time zones. Participants in the live session are expected to watch the module videos first, which can be accessed through the following links:

- Module One: Introduction to the LGBTI Inclusion Index

Video One | Video Two |Video Three| Video Four

- Module Two: How do we measure inclusion?

Video One | Video Two |Video Three| Video Four| Video Five

- Module Three: How to collect data on indicator measures

Video One | Video Two |Video Three| Video Four

- Module Four: Turning indicators and scales into a provisional index

Video One | Video Two |Video Three| Video Four

- Module Five: Data ethics and expanding data

Video One | Video Two |Video Three| Video Four

The live sessions will take place on 26 January 2022 (Wednesday) 07:00 AM Eastern Time (US and Canada) and on 28 January 2022 (Friday), 2022 09:00 AM Eastern Time (US and Canada). You can check your time zone here.

If you would like to attend the 26 January session, please register here.

If you would like to attend the 28 January session, please register here.

The trainings will be carried out by economist Professor Lee Badgett, University of Massachusetts Amherst with the following agenda:

- Introduction to the LGBTI Inclusion Index (module 1)

- How we measure inclusion (module 2)

- Finding data on the index indicators (module 3)

- Turning indicators into a provisional index (module 4)

- Next steps: building a network and expanding data (module 5)

- Final live workshop: creating an index value for your country

If you have any questions do not hesitate to contact us at boyan.konstantinov@undp.org

We look forward to seeing you at the LGBT Inclusion Index pilot training!

Senegal rejects bid to toughen strict anti-LGBT law

Senegal rejects bid to toughen strict anti-LGBT law

Read: https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/senegal-rejects-bid-to-toughen-strict-anti-lgbt-law/47240638